By Adam Browne

His name was Macaw, and he looked like one.

A pirate of Scots stock, he was fully possessed of the beakish nose of Clan Macaw, and was never without the clan plumage, or tartan, which was coloured fluorescent scarlet, cobalt blue, sun-yellow and lime green all rioted together.

Fittingly, he was the ship’s Master of Colours. In charge of flags, ceremonial displays, disguises, ornamental events and similar, he was responsible for the ship’s communications.

As such, he was the ship’s unofficial historian. ‘If ye dinnae ken her,’ he would say, ‘ye cannae speak for her!’

As such, he was the ship’s unofficial historian. ‘If ye dinnae ken her,’ he would say, ‘ye cannae speak for her!’

He loved to discover the secrets of the ship’s past, and there were many to discover, for this was the ship Vivisectress!

Yes, reader, you read that correctly! The Vivisectress!. That most notorious of pirate galleons — and most ancient! Centuries old! First a Roman trireme, in which form she saw years of warfare; with the wars ended, she was reborn as a galley. Later again, she was remade in the fashion of the Barbary corsairs. Then again — shaped into an effete French merchantship, until she mutinied against her own decorum and fled into pirate hands.

A schooner then, then a brigantine with double masts. Once a piratical floating theatre! — Cruel Theatre Vivisectress! — her hold packed with greasepaint and sets. But the actors disappeared, one by one, into the lower decks, where the ship remembered war.

Always changing. Always herself.

Each new incarnation growing on the bones of the old, her beams a collage of histories.

So each new form hid remnants of her former lives — as Macaw could attest.

‘Aince,’ he said one day, ‘I cam upon a chamber, sealed hunnerds of years, we reckon given tae the worship of sam lang-forgotten god. A sort of lizard craiture, a barbarous idol made of shadows, like… In ither quarters I found an auld messroom, strewn with shells and the strange-shaped bones o’ the beasts they ate back then, such awful leggy bogles as no langer abide in this warld…’

There was more such, and more.

For there were many discoveries, and he was a most talkative man.

Ah, reader! More than talkative! He was a squawker! Louder than his tartan!

And you know me; I cannot stand a blowhard or a braggart.

But as the most celebrated pirate-writer of my era, it was my duty to posterity, and to the West Riding Journal and Gazette of Sundry Affairs, to learn what I could of this extraordinary ship, and her pregnancy.

***

Yes, reader, you read that right, I assume!

A ship? Pregnant? How could it be? But it was! Just ask her men, as attuned to her as a spider to its web or a crab to its tidepool — and for whom the pregnancy was as unmistakable as when the top’t mizzens caught a freshening brisker off the larboard bow…

Ah, a quickening in her boards, an aliveness in her frame…

And other signs too: reports of the scents of milk and fruit-rot in her underdecks; great trails of birds and jellyfish gathering in her wake, as if waiting for birthfall…

But still!

Still, how could it be?

The answer came from Macaw.

We were working together in the fore’c’stle at the time, tri-sheeting the mainmast cornbuckler, a job that allowed time for talk. That was when I asked him.

‘Hoo can a ship get hersel pregnant, is that it?’ said he. ‘Weel, that’s no simple matter! A tangled affair! Tae even start on it, I hae tae speak first of Dutch wives, and of the Grand Duke of Venice.’

He began with the Dutch wives.

The Dutch wife, innocent reader, is a rubberised, springloaded appliance of particular design. Sometimes dressed with locks of hair, scented scraps of fabric, other marriage-materials, the device was made to ease the loneliness of the man at sea. They were, as some called them, “Wives that never get with child.”

But as Macaw said, ‘If that were so, how are we to explain the rubberised, springloaded infants that some hae seen skulking in the hold and lower decks?’

How indeed!

He then addressed the Duke of Venice, about whom Macaw was scornful. ‘He marries the Adriatic, d’ye know that? All of em hae done, through the centuries. ‘Tis an annual ritual to show the city’s dominion over the sea.’ He squawked. ‘Och, to think a marriage with dominion in it could e’er be a happy one! Look at how poorly Venice has been doin’ in recent years to see what I mean!’

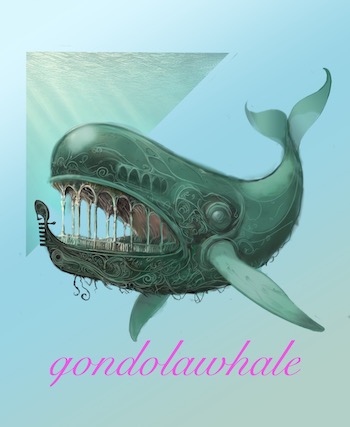

Macaw ruffled his tartan and gave another squawk. ‘But here’s this too! The dukes wed the sea, aye, and they consummate the union withal! And! — those unions hae been with issue! There’s bin progeny! Babbies, like! Don’t take it from me! Ask any sailor that has sailed the Gulf of Trieste or off the Istrian Coast; they’ll tell you about these ugsome bogles that busy about under the waves…’ He went on, describing an entire world of Venetian seamonsters; grand black gondola-whales booming above jewelled dukesfry, what ‘looped then scattered like gliffs of light in a canvas by Canaletti…

‘So, then, do ye see?’ he said. ‘If those unions proved fertile — so too the Vivisectress! ‘Twould be a wonder if it had nae happened! Jis’ think o’ the generations of men that hae been in her, all burdened with the freights of their desires, every jack of ‘em spending their dreams day and night, to seep and spill; to find a soil to sprout in. An’ the Vivisectress! is a rich soil!’

He paused, and the leather cords of the rigging, formerly whips of old Byzantium, creaked overhead.

‘But still, I cannae help but wonder… This child a-growin’ in her; this meld of mad ship and mad men, brewing in the bilgy filth-soup of the storied decks below us. I cannae help but wonder…’

Now I found myself wondering also. What was growing down there? I blinked, seeing a foetal galleon, a neonate warship with membranous sails, sin made manifest, a barbarous idol rising from pitch, made of collective yearning and bilgefilth…

Macaw was a haunted Scottish parrot, a look of trauma in its eyes. ‘What will it be…?’

![]()

About the Author

Adam Browne

Adam Browne, born in the early 1960s, lives in Melbourne.

Adam Browne, born in the early 1960s, lives in Melbourne.

He is an award-winning writer, and has published numerous sff short stories and three books.

His stories have won the Aurealis and Chronos awards, and two, 'Orlando's Third Trance' and 'Space Operetta', have been adapted as films, the latter, titled 'The Adjustable Cosmos', screened at the Sydney International Film Festival and the Anima Mundi animation festival.

'How the Ship got Heavy-Laden, by Saltpetre Cragg, Pirate and Journalist' will be part of the book 'The Ship's Big Steaming Log', which accompanies the play 'Bladderwrack", opening in Melbourne in November this year (2025).

![]()

Alistair Lloyd is a Melbourne based writer and narrator who has been consuming good quality science fiction and fantasy most of his life.

Alistair Lloyd is a Melbourne based writer and narrator who has been consuming good quality science fiction and fantasy most of his life. Tim Borella is an Australian author, mainly of short speculative fiction published in anthologies, online and in podcasts.

Tim Borella is an Australian author, mainly of short speculative fiction published in anthologies, online and in podcasts. Merri Andrew writes poetry and short fiction, some of which has appeared in Cordite, Be:longing, Baby Teeth and Islet, among other places.

Merri Andrew writes poetry and short fiction, some of which has appeared in Cordite, Be:longing, Baby Teeth and Islet, among other places. Barry Yedvobnick is a recently retired Biology Professor. He performed molecular biology and genetic research, and taught, at Emory University in Atlanta for 34 years. He is new to fiction writing, and enjoys taking real science a step or two beyond its known boundaries in his

Barry Yedvobnick is a recently retired Biology Professor. He performed molecular biology and genetic research, and taught, at Emory University in Atlanta for 34 years. He is new to fiction writing, and enjoys taking real science a step or two beyond its known boundaries in his Geraldine Borella writes fiction for children, young adults and adults. Her work has been published by Deadset Press, IFWG Publishing, Wombat Books/Rhiza Edge, AHWA/Midnight Echo, Antipodean SF, Shacklebound Books, Black Ink Fiction, Paramour Ink Fiction, House of Loki and Raven & Drake

Geraldine Borella writes fiction for children, young adults and adults. Her work has been published by Deadset Press, IFWG Publishing, Wombat Books/Rhiza Edge, AHWA/Midnight Echo, Antipodean SF, Shacklebound Books, Black Ink Fiction, Paramour Ink Fiction, House of Loki and Raven & Drake Mark is an astrophysicist and space scientist who worked on the Cassini/Huygens mission to Saturn. Following this he worked in computer consultancy, engineering, and high energy research (with a stint at the JET Fusion Torus).

Mark is an astrophysicist and space scientist who worked on the Cassini/Huygens mission to Saturn. Following this he worked in computer consultancy, engineering, and high energy research (with a stint at the JET Fusion Torus). Margaret lives the good life on a small piece of rural New South Wales Australia, with an amazing man, a couple of pets, and several rambunctious wombats.

Margaret lives the good life on a small piece of rural New South Wales Australia, with an amazing man, a couple of pets, and several rambunctious wombats. Chuck McKenzie was born in 1970, and still spends much of his time there.

Chuck McKenzie was born in 1970, and still spends much of his time there. My time at Nambucca Valley Community Radio began back in 2016 after moving into the area from Sydney.

My time at Nambucca Valley Community Radio began back in 2016 after moving into the area from Sydney. Tara Campbell is an award-winning writer, teacher, Kimbilio Fellow, fiction co-editor at Barrelhouse, and graduate of American University's MFA in Creative Writing.

Tara Campbell is an award-winning writer, teacher, Kimbilio Fellow, fiction co-editor at Barrelhouse, and graduate of American University's MFA in Creative Writing. Emma Louise Gill (she/her) is a British-Australian spec fic writer and consumer of vast amounts of coffee. Brought up on a diet of English lit, she rebelled and now spends her time writing explosive space opera and other fantastical things in

Emma Louise Gill (she/her) is a British-Australian spec fic writer and consumer of vast amounts of coffee. Brought up on a diet of English lit, she rebelled and now spends her time writing explosive space opera and other fantastical things in Ed lives with his wife plus a magical assortment of native animals in tropical North Queensland.

Ed lives with his wife plus a magical assortment of native animals in tropical North Queensland.

Sarah Jane Justice is an Adelaide-based fiction writer, poet, musician and spoken word artist.

Sarah Jane Justice is an Adelaide-based fiction writer, poet, musician and spoken word artist.